For a project on such a large scale, hundreds of artists and craftsmen were required. They worked under the supervision of masters with very different qualifications, backgrounds, talents and preferences. The Romanesque style was continued, especially in the nave which was built first, characterised by exaggerated features that give the faces a surprising expressiveness, as in the Noah, St Leobinus and St Nicholas windows. By the beginning of the 1200s we see a revival of the harmonious forms characteristic of antique Humanism, created by a desire to achieve balance, natural postures and correct proportions. Some of the finest examples of this artistic tendency are the windows of St Eustace, St Julian the Hospitaller, St James and Charlemagne.

In contrast to certain trends found in courtly circles, more modern artists opted for a starker graphic style, reducing bodies to cubic blocks that serve a narrative stripped of any superfluous decoration. This rejection of courtly convention can be seen in the St Caraunus, St Remigius and St Margaret windows. Each workshop used its own unique set of colours appropriate to the atmosphere they were attempting to create and the window’s location in the cathedral (blue is more radiant, making it more suitable for the north side, while red, which filters out light, is best on the south side). The arrangement of colours sometimes has a symbolic meaning but is more often designed to create an ornamental and artistic effect.

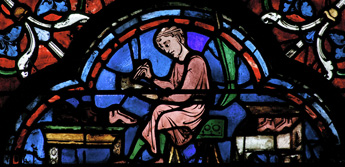

In any case, the fervent aim of all the artists was to tell a story. The stained-glass windows of this period master the art of the visual narrative brilliantly: the scenes are connected by clear transitions with contrasting systems; gestures are clear and feelings are evoked realistically, with the action situated in a reasonably detailed setting featuring trees, furniture, bridges and more. This represents a profound change in the work of the artist, who up to that point had been concerned with portraying eternal themes with no need of spatial or temporal representation. In this respect, the stained-glass windows of Chartres Cathedral are part of the humanist revolution of the 1200s, when human existence first became the subject of works of art.

The windows of Chartres bring to life the whole of medieval society with its tensions, hierarchies, preferences, its sartorial and eating habits, and more. All of the social classes and trades are represented. From birth to death, every moment of life is celebrated in gestures that are ritualised but human at the same time. Nobles show off their coats of arms, and this was something new in art. They are usually depicted dressed as knights because they wanted to be seen as defenders of Christianity. Burghers are shown in the act of buying. Images of trade and transactions play a significant part in the windows, reflecting the fact that economic activity was becoming more intense in those prosperous times. Artisans are shown working. The representation of trades in the cathedral has considerable artistic and spiritual importance. It is evidence of the new favourable attitude to man’s labour, something now seen as worthy of depiction inside a church as part of the religious narrative because it is part of the divine project of the salvation of humanity. Secular life, which until then had remained at the margins of art, now took centre stage. It may seem surprising to modern observers, but for the first time attention was paid to objects such as tools, clothing and everyday activities.